Layout

Just about every composition will involving positioning pictures. The Layout algebra provides a flexible system for handling this.

Above, Beside, and On

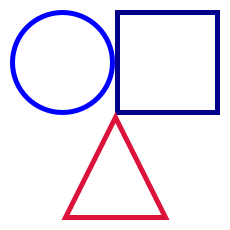

The most basic layout methods are above, beside, and on. They do what their names suggest, putting a picture above, beside, or on top of another picture. Below is an example.

import doodle.core.*

import doodle.java2d.*

import doodle.syntax.all.*

val basicLayout =

Picture

.circle(100)

.strokeColor(Color.blue)

.beside(Picture.square(100).strokeColor(Color.darkBlue))

.above(Picture.triangle(100, 100).strokeColor(Color.crimson))

.strokeWidth(5.0)Here's the output this creates.

As a convenience, there are also methods below and under, which are the opposite of above and on respectively. That is, a.above(b) == b.below(a) and a.on(b) == b.under(a)

Bounding Box and Origin

To really understand how layout works we have to understand how layout works with the bounding box and origin. Every picture has a bounding box and origin. The bounding box defines the outer extent of the picture, and the origin is an arbitrary point within the bounding box. By convention, the built-in shapes and paths have their origin in the center of the bounding box. You can position the origin anywhere you want, either by creating your own paths or using the at and originAt methods described below. If necessary, the bounding box will expand to include the origin.

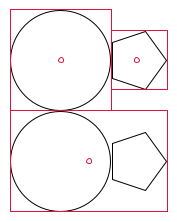

We can see the bounding box and origin using the debug method. In the example below I'm displaying the bounding box and origin of the circle and pentagon separately, above the bounding box and origin of the circle beside the pentagon.

val debugLayout =

Picture

.circle(100)

.debug

.beside(Picture.regularPolygon(5, 30).debug)

.above(

Picture.circle(100).beside(Picture.regularPolygon(5, 30)).debug

)

This gives us some insight into how the basic layout works. Using beside horizontally aligns the origins of the two pictures, the creates a new bounding box enclosing the two existing boxes with the new origin in the middle of the line joining the two origins. Above works similarly, except the alignment is vertical, while on simply places the origins at the same location.

Repositioning the Origin

The origin defines a local coordinate system for each picture, and the origin is always the point (0, 0). Changing the location of the origin is the key to creative layouts. There are two methods that do this:

at, which changes the location of the picture relative to the origin; andoriginAt, which changes the location of the origin relative to the picture.

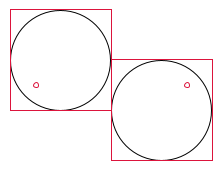

As you can see from the description, the two methods are opposites of one another. Let's see an example of use.

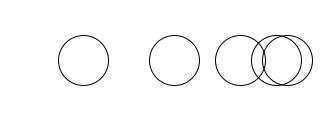

val atAndOriginAt =

Picture

.circle(100)

.at(25, 25)

.debug

.beside(Picture.circle(100).originAt(25, 25).debug)

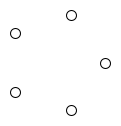

When you want to position pictures at arbitrary locations, a common pattern is to use at and on. For example, here we position five shapes at the points of a pentagon. This also demonstrates we can use polar coordinates with at.

val pentagon =

Picture

.circle(10)

.at(50, 0.degrees)

.on(Picture.circle(10).at(50, 72.degrees))

.on(Picture.circle(10).at(50, 144.degrees))

.on(Picture.circle(10).at(50, 216.degrees))

.on(Picture.circle(10).at(50, 288.degrees))

Positioning using Landmarks

Landmark provides more flexible layout, by allowing you to specify points relative to the bounding box or origin instead of in absolute terms relative to the origin. For example, we can specify the top left of the bounding box by simply using Landmark.topLeft instead of working out the coordinates of this location. Both at and originAt support landmarks.

Ultimately, all landmarks are specified relative to the origin, but you can use a percentage Coordinate instead of an absolute value. Zero percent is the origin, 100% is the top or right edge of the bounding box, and -100% is the bottom or left edge of the bounding box.

In the example below we use landmarks to specify points that are halfway between the origin and the edge of the bounding box. In this simple example we could easily work out the absolute coordinate directly, but landmarks come into their own in more complex examples.

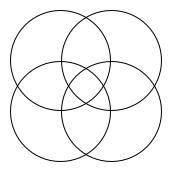

val overlappingCircles =

Picture

.circle(100)

.originAt(Landmark(Coordinate.percent(50), Coordinate.percent(-50)))

.on(

Picture

.circle(100)

.originAt(Landmark(Coordinate.percent(-50), Coordinate.percent(-50)))

)

.on(

Picture

.circle(100)

.originAt(Landmark(Coordinate.percent(-50), Coordinate.percent(50)))

)

.on(

Picture

.circle(100)

.originAt(Landmark(Coordinate.percent(50), Coordinate.percent(50)))

)

Adjusting the Bounding Box

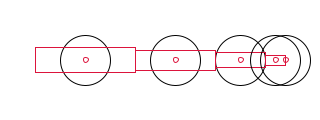

The size and margin methods allow direct manipulation of the bounding box. We will show examples below to generate this image:

We can directly adjust the size of the bounding box using size, which sets the width and height of the bounding box to the given values. These values must be non-negative, and the resulting bounding box distributes the width and height equally between the left and right, and top and bottom, respectively. Here's an example where we set the width and height to different values, and use debug to draw the resulting bounding boxes.

val circle = Picture.circle(50)

val rollingCirclesSize =

circle

.size(100, 25)

.debug

.beside(circle.size(80, 20).debug)

.beside(circle.size(50, 15).debug)

.beside(circle.size(20, 10).debug)

.beside(circle.size(0, 0).debug)

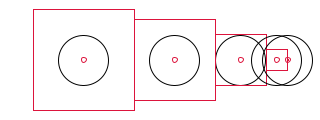

To adjust the existing bounding box we can use margin. This allows us to add extra space around a picture or, with a negative margin, to have a picture that overflows its bounding box. Here's an example that uses the form of margin that adjusts both the width and height of the bounding box. There are other variants that allow us to adjust the width and the height separately, or adjust all four edges independently.

val rollingCirclesMargin =

circle

.margin(25)

.debug

.beside(circle.margin(15).debug)

.beside(circle.debug)

.beside(circle.margin(-15).debug)

.beside(circle.margin(-25).debug)

Implementation

The Layout algebra supports all the features described above, as does Image.